Double Take - The Return of Lease Sale 258

By Hal Shepherd

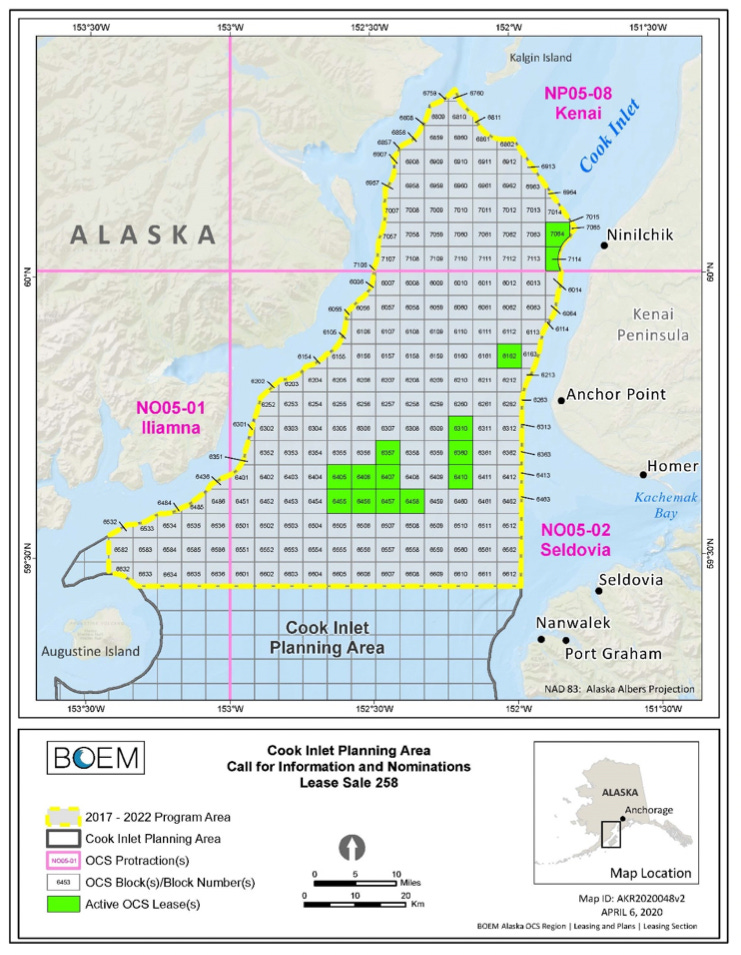

With 13 active oil and gas leases already located in Cook Inlet, a million acres in new lease sales has the potential to turn the Lower Cook Inlet into an industrial zone.

For many Alaskans that collective sigh of relief when a gridlocked Congress finally adopted the Inflation Reduction Act was short-lived. On the one hand, the Act includes $369 billion toward green energy, including wind and solar tax credits, innovation and electric vehicle incentives, and restrictions to carbon releases such as methane leak mitigation. Yet that collective leap in the air by many climate activists was cut-off at the knees when the true cost of buying Sen. Joe Manchin’s vote was laid bare. According to High County News, “with page 669 receiving the most ire: Before the federal government can issue a renewable energy right of way on public lands, it must offer at least two million acres per year for onshore oil and gas leasing.”

The irony for those of us living on the Kenai Peninsula is that the legislation does not specify were exactly, oil and gas leases are to take place, except for one location – the widely unpopular Lease Sale 258 of the Lower Cook Inlet. The region’s unique and appealing landscape is currently one of the fastest growing regions in the state and supports diverse fishing, tourism and subsistence economies, and Alaska Native cultures. Significantly, the daily currents from the Inlet serve as the life breath for numerous adjacent smaller bays, estuaries, inlets and coves - the largest of which, Kachemak Bay, is said to contain the most biologically diverse marine ecosystem in the state.

With 13 active oil and gas leases already located in Cook Inlet, a million acres in new lease sales has the potential to turn the Lower Cook Inlet into an industrial zone. Worse, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management estimates a “19% chance of one or more large oil spills occurring during 32 years of oil and gas production” resulting in impacts that “would [be] moderate for fish and marine mammals, and major for coastal and estuarine habitats and birds.” The lingering effects of the devastating Exxon-Valdez oil spill in 1989, and the months-long tragedy in the Gulf of Mexico with the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil and gas blowout highlight the challenges and inadequacy of responding to such incidents. The cold, storm-driven waters found in the marine waters of Cook Inlet along with extreme tides, winter ice, seismic activity and active volcanos in the Inlet further contribute to a high-risk scenario.

Yet, oil and gas companies, together with state agencies in Alaska, have been balking at stronger blowout prevention standards. In fact, the Department of the Interior (DOI) failed to impose a full review of potential environmental impacts of the drilling operation in the Gulf based on the conclusion from preliminary reviews of the area that a massive oil spill was “unlikely.” Similarly, according to a 2011 report by the National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and the Future of Offshore Drilling, neither “the industry’s nor the federal government’s approaches to managing and overseeing the leasing and development of offshore resources have kept pace with rapid changes in the technology, practices, and risks associated with the different geological and ocean environments being explored and developed for oil and gas production.”

Contrary to claims that such incidents are rare in Alaska, several oil well blowouts have occurred on Cook Inlet rigs since 1962, with an average of one oil spill in the Inlet per month from poor oversight of the industry and outdated pipelines.

The threats from a catastrophic spill to the unique natural resources of Cook Inlet and Kachemak Bay are now higher than ever after the industry announced plans in 2014 to sink exploratory wells into previously untapped pre-Tertiary formations containing unknown pressures. Unfortunately, existing Best Available Technology standards are inadequate to ensure that the state’s response measures are sufficient to handle a blowout in the Inlet from new wells.

Moreover, Hilcorp, which operates 11 of the 13 active drilling platforms in Cook Inlet, has a less-than-promising safety record. While BP was in the process of selling its North Slope operations to Hilcorp, Rep. Andy Josephson, D-Anchorage, prior co-chair of the House Resources and currently a member of the Finance Committee, said, "I do have concerns that they have a poor regulatory compliance record…That’s just a fact. That’s a record that’s reflected in both in the Cook Inlet and on the North Slope. It’s partly environmental and partly health and safety. They need to work harder at that….” In fact, between 2013 and 2017, the Alaska Oil and Gas Conservation Commission fined Hilcorp several times for failing to notify the Commission about changes to an approved permit, failing to obtain blowout prevention equipment, and failure to maintain a safe work environment.

Safety and environmental protection standards have largely been ignored in the rush to be the first to drill in Cook Inlet as spurred by a state law adopted in 2010 that provides a 100-percent subsidy to encourage companies to drill a well in the Inlet. This law, and other actions by industry and the state, ignore the fact that an oil spill the size of the Exxon Valdez or the Gulf of Mexico spill would devastate the premier commercial, subsistence, and sport fishing economies of Cook Inlet. The cold water environment of the Inlet would not recover from such an event, as evidenced from the still unresolved biological impacts of the Prince William Sound 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill.[1]

Similarly, on Oct. 29, 2019, the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation, (ADEC) announced a proposal to repeal well control requirements for drilling and completion operations; reserve pits and tankage; potential gas wells; common production facilities; illegal production, and open pit storage of oil. According to the Commission, “The intended effect of these repeals is to eliminate outdated, unnecessary or duplicative regulations, which have become “onerous and burdensome” to business. Critics of the changes suspect, however, that they are intended to further weaken what used to be the strongest oil and gas spill prevention laws in the country.

Robert Archibald is the president of the board of directors for the Prince William Sound Regional Citizens’ Advisory Council and has lived in Homer since 1984. Archibald spent 46 years as a mariner, including service in the U.S. Coast Guard and 32 years as chief engineer on Crowley Marine Service vessels in various locations, 22 of which were in Valdez, before retiring in 2014. He says that the Council has concerns that the ADEC review is an effort to roll back regulations to reduce the burden on the oil industry, effectively shifting that burden to the citizens and the environment of Alaska.

No wonder Lease Sale 258 has caused an outcry by Tribes, fishermen, business owners, bear viewing guides, tourists, and residents of Cook Inlet about the impacts to traditional harvest, fisheries (including Homer’s incredible halibut fishery), property values, tourism income, bear viewing sales, and the ongoing climate emergency. In fact, when BOEM originally proposed the lease sale, there were only nine comments submitted that supported the sale as opposed to tens of thousands in opposition. According to Liz Mering, former Advocacy Director for Cook Inletkeeper based in Homer, “It is incredibly disappointing to learn that Alaskans and Americans are being ignored because of the influence that Outside industry has on politicians in D.C.” [2]

Alas, regardless of strong opposition, and despite being canceled by BOEM due to lack of industry interest earlier this year, Lease sale 258 must happen before the end of the year because it is part of a congressional mandate. It is still possible, however, to mitigate the impacts from future lease sales. For starters, the Department of Interior is proposing more offshore oil and gas leases (other than Lease Sale 258) in federal waters including one proposed in Lower Cook Inlet from 2023 through 2028. You can speak out for the protection of the Lower Cook Inlet and Kachemak Bay Watersheds during the open comment period on the proposed five-year plan, by signing a petition asking President Biden to withdraw the federal waters of Cook Inlet from all future offshore oil and gas lease sales, or write letters to the editor or op-eds to your local newspaper.

For more information or the full list of actions you can take see the Cook Inlet Keeper web page on the 5 year plan. If you need additional guidance to write a Letter to the Editor, contact satchel@inletkeeper.org.

[1] Rebbecca Luczycki, The State of the Sound, Twenty Years After the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill, the Recovery of Prince William Sound is Still the Subject of Debate, Alaska Magazine, p. 22-31 & 75 (September 2009).

[2] Liz Mering, PROPOSED BILL IN CONGRESS IGNORES ALASKANS, WOULD SACRIFICE COOK INLET, CIK NEWSLETTER (JULY 28, 2022).