Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy announced earlier this month that the state is taking control of navigable waters from the federal government. According to Dunleavy, ever since statehood, the feds have refused to accept the fact that the U.S. Constitution also grants new states ownership of the navigable waters and submerged lands inside their borders. The Governor stated that the federal government has “dragged Alaska through a costly, multi-year process – for each waterbody – to get what has been ours since 1959. They oppose our claims at every turn, ignoring procedures and common-sense compromises that could dramatically speed the process.”

This “costly, multi-year process” can only be a reference to the state and Alaska Native land claims selection process that started in 1959 and continues to this day. Rather than “oppose our claims at every turn” as suggested by the Governor, however, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management actually sided with the state to prevent Alaska Native claims land selections for the same lands that the state wanted. Once the tribes organized and stood up for their rights, the Department of Interior sided with them until Congress adopted the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANSCA) which eliminated the Tribe’s rights to make such claims and handed them over to Native corporations. ANSCA also directed the Secretary of Interior to set aside millions of acres of land from which the state and Native corporations have been making land selections since the Act was adopted in 1971.

Never-the-less, Dunleavey says “I am asserting the state’s control of the navigable waters and submerged lands we received at statehood, and our right to manage them in Alaskans’ best interests.” He relies on several legal principles for this claim, including the U.S. Constitution’s “equal footing doctrine,” which gives new states the same rights to beds and banks of navigable waters as existing states, and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act which in some cases, exempted state and private water from federal regulation regarding national parks, preserves, forests, or monuments.

According to Dunleavy, despite this “clear legal evidence and repeated losses at the Supreme Court” the federal government has refused to acknowledge Alaska’s ownership of waters within its borders. While the Governor does not specify what repeated losses at which Supreme Court he is referring to, one thing is clear - the U.S. Supreme Court has consistently rejected complete ownership of water by either the federal or state governments. In fact, while in most cases, navigable waters located within the Alaska’s borders come under state jurisdiction, through an interim memorandum of agreement, Alaska coordinates with the federal government to oversee subsistence fisheries and wildlife management on federal lands such as national parks, national forests, and wild and scenic rivers.

Yet Dunleavy, seems to believe that despite the Supreme Court’s position on the issue and this agreement, the state should assert state complete ownership over navigable waters solely because of a single Supreme Court opinion. He says that:

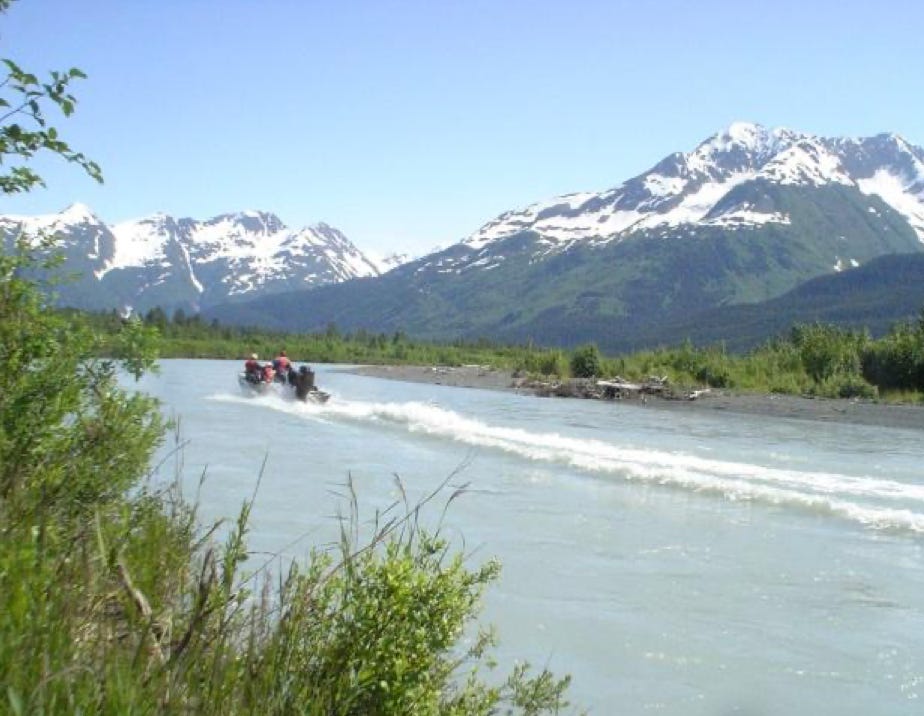

The Sturgeon case, however, focused on the narrow issue of whether the state or federal government had jurisdiction over the navigable waters of the Nation River located within the Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve near the Canadian border. The US Supreme Court concluded that, for the purposes of ANILCA the river does not qualify as “public land,” and therefore, the Park Service did not have the authority to regulate Sturgeon’s activities on the part of the river found within the preserve. Not only, therefore, does the Sturgeon case not affect other waters located within federal lands in Alaska but the Court said it does not even completely eliminate federal regulatory jurisdiction over such rivers based on its finding that its decision does “not disturb the Ninth Circuit’s holdings that the Park Service may regulate subsistence fishing on navigable waters.”

It appears, therefore, that Dunleavy’s praise of Sturgeon who single handedly dismantled environmental protections in one national Park so that he could gain motorized access via hovercraft to a remote and pristine area for moose hunting, is a remnant of the sagebrush rebellion theme of the 70-80s in the Western U.S. championed by the far right who were accustomed to using public-land resources as they wished. As in the case of Dunleavy’s attack on federal environmental regulations, the rebellion was in response to federal public-land laws and policies design to protect fish and wildlife and the interest of Indigenous communities including the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, Wilderness Act and Endangered Species Act and treaties with tribes.

The Sagebrush Rebellion, therefore, gained steam after “such westerners no longer got what they wanted,” and are characterized by baseless attacks on federal officials attempting to enforce legitimate federal regulations. The movement also inspired right wing terrorism such as when ranchers claiming they had a right to graze cattle on federal land, forced federal authorities to withdrew after being outgunned by militiamen at Bunkerville, Nevada in 2014 and the 2016 armed paramilitary take over at the Malheur Wildlife Refuge field station in Oregon.

Dunleavy’s claims, therefore, that “Alaska’s destiny lies in full ownership of our natural resources,” and that his “actions are a first step in ‘Unlocking Alaska,” does seem consistent with historical right-wing resistance to “any attempts at an ambitious federal public-land policy. ” The Governor even vows that “the State will provide a legal shield to Alaskans for as long the Biden administration wishes to lose cases” although to date the Biden administration has yet to voice any intention of engaging in any water rights litigation regarding Alaska. The Governor’s Sagebrush Rebellion sympathies are also illustrated by his administration’s elimination of bans on jet-skis and attempts to open up state critical habitat areas to the extraction industry, and selling millions of acres of state land to private interests.

So, when the Governor says “[f]or too long, we have waited for federal land managers to fulfill their duty and acknowledge that Alaskans, not federal bureaucrats, are the true owners of Alaska’s navigable waters and submerged lands.” what he really means is that he wants to remove environmental protections that are meant to protect these resources for all Alaskans and hand them over to the resources extraction industry including outside and foreign corporations. This is best illustrated by his administration’s current efforts to prevent the state’s citizens and tribal governmental entities from keeping instream flows intact in order to protect subsistence resources and his efforts to fast track environmental analysis for mining permits.